Rockbridge Academy Blog

Faith in Action: Following Christ After College

.JPG)

For the past nine months, I have been learning what it looks like to live as a Christian after college. I participated in the Capital Fellows Program at McLean Presbyterian Church in Northern Virginia. It is a leadership and discipleship program for recent college graduates, focusing on vocation, community, service, and leadership. In this article, I hope to share with you some of what I learned during this year of living out faith and work.

"When he had washed their feet and put on his outer garments and resumed his place, he said to them, 'Do you understand what I have done to you? You call me Teacher and Lord, and you are right, for so I am. If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another's feet. For I have given you an example, that you also should do just as I have done to you.'" John 13:12-15.

There I was, at church like I was every Monday evening, surrounded by my 12 peers. Our program director, John Kyle, also sat in the room and had just read us this passage from John 13. We were talking about leading like Jesus. Familiar with this passage where Jesus washes his disciple's feet, I thought I knew where he was going. And in some ways, I was correct. In order to lead like Jesus, we need to serve one another. We spoke often of this throughout the duration of the Capital Fellows program. Christian leadership requires serving others out of a Chirstlike love for them and the knowledge of their dignity as fellow image bearers.

What I didn't see coming though, was what happened next. John Kyle's wife opened the door and pushed a cart full of pitchers with warm water, empty basins, and folded white towels into the room. John Kyle grinned and said, "Now we are going to give you all the opportunity to literally wash one another's feet." We all looked around, and slowly moved towards the cart full of supplies. I had grown to love these people over the last seven months, but washing their feet still seemed uncomfortable. The idea of serving them was super easy in my head, but when it came time to actually wash their feet and have my feet washed, I was hesitant. However, the evening turned into a sweet hour of washing feet and prayer. I never would have expected this.

I share this story with my Rockbridge community not to encourage you to go get a pitcher and literally wash feet (though I guess that worked for me). I share it more so as a reminder that serving like Christ requires action. At Rockbridge, we learn about taking every thought captive in obedience to Christ. However, we must not stop there. In our learning we take every thought captive to obey Christ, and in our living we must take everything as an opportunity to lead and serve like him.

Throughout the program, fellows work a paid internship in their field of choice, take seminary classes, serve in the community and in church, read through the entire bible, have group discussions on various topics, receive Christian career mentorship, and live with host families. Instead of just talking about how to live a Christian life after college, this year gave me the opportunity to do it.

Throughout the program, fellows work a paid internship in their field of choice, take seminary classes, serve in the community and in church, read through the entire bible, have group discussions on various topics, receive Christian career mentorship, and live with host families. Instead of just talking about how to live a Christian life after college, this year gave me the opportunity to do it. Yet I learned that "doing it," putting faith in action, is impossible without Christ.

With all that this year required, at times I lost sight of Jesus. During those times, my joy for my work came and went, my eagerness to be in community lessened, my desire to serve dwindled, and my leadership suffered. Even though they brought hardship, I am thankful for those moments. Through them I realized that without Jesus, every aspect of life loses its meaning! I need Him. We all do. I often thought of Galatians 2:20 this year. It says, "I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me." As a Christian I am not the one living. It is Christ that lives in me. He loved me and gave himself for me. So I live my Christian life by faith in his work in me and through me.

Capital Fellows was not the first place that I learned about living life as a Christian. Rockbridge laid the foundation. I remember singing the Alma Mater at the beginning and end of each school year. Asking God to be in my head, eyes, mouth, and heart. I was often reminded that the work I was doing was not for myself, because God was the one working through my head, heart, and hands. Rockbridge is full of hard-working students and parents that love Jesus and live out their faith in a way that honors God. However, in the hustle and bustle of school, it is easy to lose sight of the Savior, even though he is the one that is living in us!

The Capital Fellows program gave me more intentional opportunities to practice putting my faith in action, pointing me to Jesus. This practice is something I will need for my whole life. When we fix our eyes on Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, we will live out opportunities to live and serve like Him. Because of Jesus, we have joyful purpose in work, have eyes to see the dignity of others in community, have hearts with zeal to serve, and have guidance and wisdom in leadership in all stages of life.

If you are interested in hearing more about Capital Fellows, feel free to contact Sarah Williams (sarahkwilliams17@gmail.com). For more information and to apply, click this link: https://www.capitalfellows.org/apply

Sarah Williams (Rockbridge Academy Class of 2020) graduated from Clemson University in May 2024, completed Capital Fellows this year, and she will be starting graduate school at George Washington University in August for occupational therapy.

From Dragons to Disciples: What Lewis and Tolkien Teach Us about Making Disciples

Christ’s command to his apostles to go and make disciples (Matt. 28:16–20) is intended for all his followers. Every Christian must think carefully about what it means to be a disciple of Jesus and to make a disciple of Jesus. Though the commission remains unchanged since Christ first uttered it, each new generation encounters contexts and challenges for discipleship that are both old and new. This reality becomes clear if we look at the youth in our society and begin to ask how we might best form them into disciples of Christ. There has been an alarming, well-documented rise in loneliness, depression, anxiety, mental health disorders, and suicides among children and adolescents over the last two decades—not to mention “the great dechurching.”1 For me, as a high school teacher and a parent of young children, these trends are particularly terrifying. How do we make disciples of children who might be struggling with debilitating depression or doubts? How do we make disciples in a context where these increasingly common struggles press on us as parents and teachers alongside all the typical struggles of being sinful human beings making disciples in a fallen world?

Consumer or Contributor?

Recently, I was struck by an interesting observation from counselor and therapist Keith McCurdy. In over three decades of working as a therapist, he has found that a person’s mental health generally correlates to where they fall on a sliding scale from “consumer” to “contributor.”2 The farther down the consumer side, the less healthy they tend to be. I wondered, could McCurdy’s observation shed light on how we as Christians think about making disciples—especially of our children?

Since we believe we’re creatures made in the image of a creating God, McCurdy’s observation should come as no surprise. But we often forget a fundamental fact about being human: We were created to create. We exist to “glorify God and enjoy him forever,” as the Westminster Shorter Catechism famously puts it; a key part of our calling to bring glory to God is to bless our neighbors, to contribute in productive, valuable, meaningful ways to our communities. Adam was commanded to fill and subdue the earth. He was to be fruitful and multiply, creating a community that would exercise dominion over creation. However, Adam chose a shortcut to knowledge. Instead of learning through experience over a period of time, he sought to gain the knowledge of good and evil through a single bite. He would not earn or create knowledge. He would, literally, consume it. In fact, the Latin root for our word consume, consumere, means “to eat.” God had blessed Adam with all he needed for life, but he chose to reject God’s provision and consume the fruit. By this choice, Adam condemned and corrupted himself and his posterity. Evil entered the world. The image of God was broken and polluted by sin.

For us who live east of Eden, we’re tempted to believe that we exist primarily to consume rather than contribute something good to the world. In believing this lie, we too have become less human than we ought to be. It’s no wonder so many spiritual, mental, and relational maladies have skyrocketed in a culture that not only enables but encourages the acquisition of material wealth and pleasurable experiences more than perhaps any before us in history. In fact, modern society often deems the possession of wealth—whether in the form of money, prestige, a “following,” or experiences—as the ultimate sign of greatness. What we consume may not always be forbidden fruit, but it just as easily tempts us to believe it will make us “like God.”

Becoming a Dragon

These thoughts floated about in my head as I drove to work one morning listening to J. R. R. Tolkien’s much-loved story The Hobbit. I was struck by dwarven king Thorin Oakenshield’s description of dragons:

“Dragons steal gold and jewels, you know, from men and elves and dwarves, wherever they can find them; and they guard their plunder as long as they live (which is practically forever, unless they are killed), and never enjoy a brass ring of it. Indeed they hardly know a good bit of work from a bad, though they usually have a good notion of the current market value; and they can’t make a thing for themselves, not even mend a little loose scale of their armour.”

In Tolkien’s Middle-earth, dragons are the ultimate consumers. They hoard their treasure for the sole purpose of possessing it. They don’t offer anything to society; they take all they can and give nothing in return. They don’t enjoy their plunder, either, since they have no ability to discern good from bad or beautiful from ugly. All they seem to care about is more—how much they have and how much it might be worth.

Tolkien’s description of a dragon feels eerily familiar. How often do we approach life and work with the goal (or at least the secret desire) to accumulate wealth far beyond what we realistically need for a stable and enjoyable life? Every time we justify less than honest means of acquiring something, we become more dragon and less human; every time we store up wealth from selfishness or insecurity, we become more like Smaug sprawled jealously over his treasure hoard. The more we’re focused on amassing and consuming, the less we’re able to contribute truth, beauty, and goodness to the lives of those around us.

Tolkien’s friend and fellow Oxford don C. S. Lewis illustrated the dark reality of being consumed with consumption in a poem called “The Dragon Speaks.”3 In the poem, the dragon tells us his life story. He recalls hatching from his egg, “I came forth shining into the trembling wood,” and reminisces about his “speckled mate” whom he loved. This love, however, did not stop him from eating his lover—one of his great regrets: “Often I wish I had not eaten my wife.” Yet we discover the dark reason for the dragon’s remorse: eating his wife left him with sole responsibility for watching over his gold. He never sleeps; he only leaves his cave three times a year to take a drink of water, terrified someone will steal from him. He becomes a prisoner in his own home, a captive of greed and fear. The poem closes with a dark and malevolent prayer:

They have not pity for the old, lugubrious dragon.

Lord that made the dragon, grant me thy peace,

But say not that I should give up the gold,

Nor move, nor die. Others would have the gold,

Kill rather, Lord, the Men and the other dragons;

Then I can sleep; go when I will to drink.

The dragon’s obsession with his gold turns him into a murderous, lonely, pathetic character. His speech leaves us not in terror but full of pity for his sad existence. His obsession with treasure, his consumerism, has left him nothing but selfish anxiety. While our children’s frequent anxiety, loneliness, fear, and cynicism may not be directly caused by a personal dragon-like consumer mentality, they are certainly indirectly suffering the effects of such a mentality in the culture all around them.

This has important implications for discipling them. At the very least, we must teach and train our children to hold loosely to the things of this world. They must see them rightly: as good gifts from God, but not as ends in themselves. God is the ultimate good. Communion with him is the true goal. God’s kingdom is greater than ours. And, of course, forming our children into disciples that seek God’s kingdom, first and foremost, starts with our personal example. We will struggle to make disciples of Christ if we ourselves are more dragon than disciple.

Jesus and Dragons

Jesus warned us about the danger of becoming dragons. He told a story about a rich man who was a wildly successful farmer (Luke 12:16–21). The man had no place to store the enormous harvests he was enjoying year after year; so each time his barns got full, he decided to level them and build bigger ones in their place. Afterward, the rich man, feeling safe and secure, congratulated himself: “Soul, you have ample good laid up for many years; relax, eat, drink, be merry.” Yet as soon as the words come out of his mouth,“God said to him, ‘Fool! This night your soul is required of you, and the things you have prepared, whose will they be?’” Jesus concludes his parable with this pithy moral: “So is the one who lays up treasure for himself and is not rich toward God.”

A truly rich life is one lived each day to the glory of God by loving him and our neighbor—not only with our hearts, words, and actions but also with our possessions. It’s foolish—dragonish—to live for material consumption amid spiritual poverty.

C. S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, part of The Chronicles of Narnia series, also contains a parable about a dragon—but one whose story doesn’t end so hopelessly.

The Parable of Eustace Clarence Scrubb

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader has, in my estimation, one of the best opening lines in all fiction: “There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.”4 Eustace is an insufferable brat. He has no friends; he only likes books that contain information (not stories); he enjoys bossing and bullying. In the story, Eustace enters the world of Narnia through a painting of the title boat, the Dawn Treader, along with two of his cousins (Edmund and Lucy). The three children board the ship and embark on a series of adventures.

During one adventure, Eustace encounters a dragon in its final moment of life. A sudden storm forces Eustace into the dragon’s lair, where he discovers its hoard (all of this is very much to his surprise because he never read the “right books,” which would have taught him all about dragons). Upon discovering the treasure, Eustace begins to imagine “the use it would be in this new world [Narnia]. . . . With some of this stuff I could have quite a decent time here.”5 Notice how Eustace thinks of his newfound wealth: not as something to enjoy with others or even something intrinsically beautiful. It is merely a means to be used for selfish pleasure. Eustace sounds like a dragon. In fact, after sliding a bracelet from the dragon’s hoard onto his bicep and falling asleep, he slowly awakens to the horrible realization that he has become a dragon himself!

For Lewis, this is both Eustace’s low point and his turning point: “He began to see that the others had not really been fiends at all. He began to wonder if he himself had been such a nice person as he had always supposed.”6 For Eustace, to know he is a dragon and to become self-aware of his own true character are one and the same. This newfound self-awareness leads Eustace to find ways to contribute to the crew of the Dawn Treader. One lesson we can take from this is that in order to form children into disciples of Christ, we should proactively seek to make them into people who see and respond to the needs that are in front of them, to emulate Christ by loving their neighbors as themselves.

It is interesting that the biblical command to love our neighbor as ourselves rests on an assumption that we love ourselves in the first place. As we think about making disciples of the younger generation, this presents a unique challenge. To youth prone to anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation, self-loathing is often a more familiar experience than self-love. In discipling children, we must help them to love themselves. We don’t do this by boosting their self-esteem through unearned trophies or telling them they aren’t sinful. Since we’re all dragons by nature, let’s not pretend otherwise—and let’s not pretend self-centered consumption is praiseworthy rather than destructive for disciples of Christ. Rather, let’s help our children form a stable identity in Christ, the ultimate contributor.

In his lecture, Keith McCurdy also argued that to know our identity, we must be able to answer three questions: Am I valuable? Am I capable? Am I part of something bigger than myself? We must help our children identify their abilities, develop their skills, and discern their gifts. The more we find ways to help our children see themselves as servants of Christ, lovingly serving their community as a response to his love with the gifts and resources he has given them, the more they will be able to love themselves. But not because they’re narcissists and not because they think they’re perfect. The heart of discipling our children is teaching them that God loves them despite their sin and rebellion—that Christ has slain the Dragon and is transforming them from dragons to disciples. Again, the story of Eustace illustrates this well.

The “Un-Dragoning” of Eustace

One night, while in dragon form, Eustace is visited by a lion (Aslan, though Eustace did not know him yet). The lion leads him to a well deep in the mountains and tells Eustace he must undress before he can bathe. Eustace is puzzled at first, but then realizes that the lion is telling him to shed his skin. So Eustace scrapes off a layer of scales as a snake would shed its skin. This only reveals another layer of scales that needs to be scraped off. After three times of trying to get his dragon-skin off, Eustace realizes he cannot undress himself. At this moment, the lion intervenes and says, “You will have to let me undress you.”7 With his claws, the lion tears deep into Eustace, inflicting horrible pain but fully removing the dragon skin. Then, without warning, the lion grabs Eustace and tosses him into the water. As he swims about, Eustace becomes a boy once again. This part of Eustace’s story illustrates the final and most important piece to making disciples: Following Christ means we repent, we kill sin, we place our faith in Christ, and we live as a new creation.

To be rich toward God (and, by extension, the communities he places us in), we must become dragon slayers by putting to death the sinful inclinations in our hearts to love and hoard the things of this world over God and his kingdom. In place of our old dragons, we must put on the mantle of Christ, the ultimate contributor who gave all he had to offer, indeed his very life, that we might be called into the family of God. Ultimately our children, like us, need the gospel. We make disciples by modeling, teaching, and giving opportunity for our children to apply the gospel in their lives.

Christ the Consumed

Our relationship with God is broken by our sin. We are a good creation of God, but by our choices we corrupt ourselves. Like Eustace, we have become dragons and, while we can be better and worse dragons, we cannot “un-dragon” ourselves. For that, we need divine intervention. As Eustace needed Aslan, we need Christ.

The fallen state of humanity is far worse than we might initially imagine. Not only are we consumers who use and twist the good creation of God for our own selfish purposes, but we also attempt to contribute in all the wrong ways. The apostle Paul described this reality well: “For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh. For I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing” (Rom. 7:18–19). This is where Christ comes in. He is the perfect contributor on our behalf. Christ succeeded where Adam failed. He obeyed God and his law perfectly. This obedience meant that Jesus deserved God’s love and blessing, but instead Christ bore the wrath of God and the curse for sin. On the cross, Christ was consumed in our place. This becomes clear in one of John’s visions from the book of Revelation.

John writes, “And the dragon stood before the woman who was about to give birth, so that when she bore her child he might devour it. She gave birth to a male child, one who is to rule all the nations with a rod of iron, but her child was caught up to God and to his throne” (Rev. 12:4–5). The child who is to rule the nations with an iron rod is Jesus Christ, the Son of God and the Messiah (see Ps. 2:7–9). Satan is pictured here as a dragon waiting to consume Christ—and in a sense, he does. On the cross, the Son of God dies. The one who is life is swallowed up by death, and it looks like Satan has won. Yet, in his death, Christ defeats Satan. The dragon does not win. Christ is not held captive by the grave. He comes back to life and ascends to the right hand of God.

This turn of events is what Tolkien described as an eucatastrophe—that is, a good catastrophe. It may seem odd to call a catastrophe good, but Tolkien argues that “the eucatasrophic tale is the true form of fairy-tale, and its highest function.”8 In the Gospels, Tolkien writes, we find “the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe.”9 There is no greater tragedy than the unjust execution of the Son of God and no greater good than the salvation that came about as a result of Christ’s death. The staggering thing about the Gospels, however, is that “this story has entered History.”10 In other words, it really happened!

Making Disciples

This has staggering implications for what it means to be and to make disciples of Christ. Because Christ conquered Satan, sin, and death, we can as well. Not in our own strength, of course, but in his: “If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ Jesus from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit who dwells in you” (Rom. 8:11). The indwelling Holy Spirit ensures that Christ’s disciples will be conformed to the image of God. The Spirit takes dragons and makes us disciples who seek to kill the sin that dwells within us and live as a new creation freely sharing our treasure with others. Of course, this doesn’t happen overnight. One last time, let us consider post-dragon Eustace:

It would be nice, and fairly near true, to say that “from that time forth Eustace was a different boy.” To be strictly accurate, he began to be a different boy. He had relapses. There were still many days when he could be very tiresome. But most of those I shall not notice. The cure had begun.11

Christ is the cure, but he does not cure us in a moment. We must take the long view with our children. Their faith, mental health, or sense of identity will never be perfect or impervious. However, God will use us to finish the good work he has begun (Phil. 1:3). God could make disciples without us, but he chooses to work through our efforts. To make disciples, we must first be disciples. Furthermore, to feed Christ’s sheep, we must first be fed. It is no wonder that Christ invites us to consume his body and blood at the Lord’s Supper. Through this meal, the Spirit channels the grace of God to us. When we feed on Christ, and only then, will we have the love necessary to make disciples of others. That is, after all, what discipleship is at its core. It is an act of love, an involvement in another person’s life in which we desire to contribute wholly to their good rather than view them as an object to be used, exploited, or consumed.

In short, the more we encourage and provide opportunities for our children to contribute to the community God has placed them in, the more we teach them to seek the kingdom of God (by our word and deed); and the more we help them to form their identity in Christ, the better their spiritual and mental health will be. By God’s grace, they will transform from dragon to human, from consumer to contributor, “rich toward God” and neighbor through the generosity of the one who not only slays dragons but gives them true life.

Andrew Menkis (BA, philosophy and classics, University of Maryland; MA, historical theology, Westminster Seminary, California) is a high school Bible teacher at Rockbridge Academy in Crownsville, MD. He is passionate about teaching the deep things of God in ways that are understandable and accessible to all followers of Christ.

This article was first published in Modern Reformation in July 2024.

Footnotes

1. “Child and Adolescent Mental Health,” 2022 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality US); National Library of Medicine, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587174/.

2. Keith McCurdy, “Raising Sturdy Kids,” lecture given at Rockbridge Academy, Crownsville, MD, February 2, 2024.

3. C. S. Lewis, Poems (New York: Harvest / HBJ Book, 1964), 92–93.

4. C. S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (New York: HarperTrophy, 1952), 3.

5. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, 87.

6.Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, 92.

7. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, 108.

8. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays (London: HarperCollins, 1983), 153.

9. Tolkien, The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, 156.

10. Tolkien, The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, 156.

11. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, 112.

Dragon Stock photos by Vecteezy and Pile Of Gold Stock photos by Vecteezy

Whimsy, Joy and Witness! The History of Rockbridge Academy PE

“We would do it differently, or it wouldn’t be worth doing.” That was the attitude that permeated every effort and initiative of Rockbridge Academy’s founding families. This included PE—physical education. The phrase is almost redundant, as if education itself is ever apart from the body. Certainly that was the understanding of our founding families, who determined to provide an integrated education, a classical, christian education which would affirm Colossians 1:17: that all of life was created through Christ and is held together and sustained by Him.

“We would do it differently, or it wouldn’t be worth doing.” That was the attitude that permeated every effort and initiative of Rockbridge Academy’s founding families. This included PE—physical education. The phrase is almost redundant, as if education itself is ever apart from the body. Certainly that was the understanding of our founding families, who determined to provide an integrated education, a classical, christian education which would affirm Colossians 1:17: that all of life was created through Christ and is held together and sustained by Him.

The Scriptures are rife with analogies of the how the body informs the mind and vice versa (Mark 12:30, Prov. 3:7-8, James 3:2, to list a few). In a fallen world that continually tries to dis-integrate what God has integrated, it may seem radical to affirm, as the vision for Rockbridge PE does, that, “God is Sovereign to mysteriously work in the physical world and produce spiritual results. This is most evident in the physical death of the God-man, incarnate to bring about spiritual redemption and new life. Since God has seen fit to integrate the material and the immaterial, the visible and the invisible, we should strive to teach our children that God is glorified in how they use their bodies, as well as their minds and spirits.”

God is glorified when we are good stewards of our physical bodies. In a classical and Christ-centered school, children should be taught how to move skillfully, how to play strategically, and how to exercise consistently and expressively. Our goal in physically educating our children should be that they would be like David, the poet-warrior, who ‘danced before the Lord with all his might’” (II Sam. 6:14).

A little further along in our PE curriculum it reads, “According to the Westminster Catechism, ‘The chief end of man is to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.’ This enjoyment includes physical pleasures such as rolling down a grassy hill, running an invigorating five miles, playing a game of tag, or walking as a family after dinner, all while caring for all aspects of the body. God is glorified when we are good stewards of our physical bodies. In a classical and Christ-centered school, children should be taught how to move skillfully, how to play strategically, and how to exercise consistently and expressively. Our goal in physically educating our children should be that they would be like David, the poet-warrior, who ‘danced before the Lord with all his might’” (II Sam. 6:14).

Did you catch that? These words are written in Rockbridge Academy’s PE curriculum? Reading over these pages again recently, I was reminded of the beautiful vision that was set before me 21 years ago, when Donna Griffith, co-author of this curriculum, PE teacher at the time, and Rockbridge Academy's first Athletic Director, invited me to apply to teach PE at Rockbridge. In that moment, I had no idea how God would use me, only that I was being invited to participate in a distinctive, counter-cultural movement called, “Classical Christian Education,” and one that I had already decided I wanted for my own children.

Donna Griffith mentored me in those days, along with Amy Marshall (who was recognized in the last Benedictio for reaching her 25-year milestone at Rockbridge). Donna’s background and training was in PE, and she had been a college athlete, so when she envisioned PE and athletics from a godly perspective, she knew exactly what they would be distinguished from. PE at Rockbridge would be taught from the Trivium—those three particular stages of development that align so clearly with the growth and development of each child. Her description reads, “Physical Education in the Grammar school helps students become proficient in basic movement skills. In Dialectic, the children refine the skills learned in grammar school and apply them while playing a variety of individual, dual, and team sports. Students also receive instruction in strategies and rules. In Rhetoric, the students continue perfecting their skills in a variety of sports while learning about strategy.” In a recent phone call, Donna recollected that, “This idea was very unique to our school, [the idea that] the playing field is to PE what the chemistry lab is to chemistry.” Children’s knowledge and understanding are used to put on a beautiful display—whether that is exploration and discovery in a lab, in making music or art, in giving a thesis speech, or playing in an athletic competition. Donna went even further in describing this vision as “whimsical,” the desire for our children to have “beautiful coordination” and “majestic and lovely” movement. Whimsy? Yes, of course! When our children fully realize a godly vision in any endeavor, it brings joy—whimsy—the foretaste of Heaven.

Amy Marshall, who taught upper school PE for several years in those early days, may have had this notion in mind when she decided to teach her students ballroom dancing! Most of what she remembers from teaching in those early years was that, “We were aiming at skills acquisition, training men and women according to their frame, being earnest about shaping our 'earthen vessel' to serve God well, and so on.” But it was the ballroom dancing unit that quickly spilled over from her PE students to the rest of the student body. Soon non-PE upper school students were streaming into the gym. Ballroom dancing gave way to swing dancing, and learning that ultimately led to a performance in the Rockbridge Academy Variety Show. And it started with the fun, the delight, of movement in PE class!

If you have read this far, I hope you are encouraged, even inspired by the vision that informs your child’s physical education and athletic participation at Rockbridge Academy. But, I would be remiss if I didn’t elaborate on one additional distinctive. Our PE vision goes on to say that, “Physical education is unique in the opportunities it provides for character development. Physical activities and competition often trigger emotions that aren’t exhibited in the classroom.”

Physical education is unique in the opportunities it provides for character development. Physical activities and competition often trigger emotions that aren’t exhibited in the classroom.

That description sounds a lot like an idea often attributed to Plato suggesting that, "You can discover more about a person in an hour of play than in a year of conversation.” (You can google the quote later for an interesting read on its disputed origin, but I think the essence of the meaning has been accurately preserved.) I can affirm this sentiment from first-hand experience! A game of dodgeball—or basketball, or soccer, or tag or "Sharks and Minnows”—brings out emotions seldom seen during a spelling test or classroom discussion.

So that, “The physical educator has the privilege of teaching the children what God has to say about their emotions and how they should respond to those emotions. The goal of the classical and Christ¬ centered physical education program is to have students exhibit self-control and humility as they play to the best of their God-given ability.”

The goal of the classical and Christ-centered physical education program is to have students exhibit self-control and humility as they play to the best of their God-given ability.

This kind of training, this shaping of character, becomes evangelistic. Our athletic handbook states, “While winning is valued, at Rockbridge Academy, the overriding emphasis is on building the Christian character of our student athletes…Sportsmanship, teamwork, fair play, and the value of hard work are valuable life lessons that can be learned through competitive athletic participation. [Athletic] games afford an opportunity for Rockbridge athletes to act as ambassadors for Christ..[to] show respect and appreciation for our opponents, officials, and coaches.” Of course, for, “We are therefore Christ’s ambassadors, as though God were making His appeal through us.” 2 Cor. 5:20. This is always our first and most important objective as Christians in any endeavor we pursue.

Sportsmanship, teamwork, fair play, and the value of hard work are valuable life lessons that can be learned through competitive athletic participation. [Athletic] games afford an opportunity for Rockbridge athletes to act as ambassadors for Christ...[to] show respect and appreciation for our opponents, officials, and coaches.

Where this vision takes hold of each student, and is brought to fruition by the Holy Spirit, our graduates, whether in a professional stadium, in a collegiate competition, on the neighborhood pickle ball court, or any other area of play, will look very different indeed. Ok, let’s play!

Melanie Kaiss has taught PE at Rockbridge Academy since 2004. She began teaching when her oldest child was in second grade. All four of her children have since graduated from Rockbridge (Classes of 2015, 2016, 2018, and 2024). Over the last 21 years, Melanie has taught PE at every grade level, been assistant to the Athletic Director, coached girls soccer and lacrosse, and run numerous Discovery Summer camps for five years running. Melanie’s husband, Stephen, joined the Rockbridge board shortly after she began teaching. He became a permanent board member and continues to serve today.

Further Up and Further In—Library Stories of Life Together

Boxes of books—moved and unpacked by many hands. That is how the present Rockbridge library began. Oh, make no mistake, Rockbridge always had a library, even before there was space for one. Great books have always been a defining thread in the culture of Rockbridge. It’s just that the books had to be placed on carts, in corners, on classroom shelves or tables, or wherever they could be safely tucked away and retrieved for use at suitable times. Now, however, over 10,000 books line the shelves of the school library, at the ready. The library still feels like a new attraction to many upper school students since the grand opening in September of 2022. Many grammar school students, on the other hand, will retain no memories of school without a library. As alumni wandered the halls before Christmas break during the Captain’s Cup, a few stepped into the library and one declared, “I am so jealous they have a library!” We don’t have books for the sake of having books, however. Stories bring us closer to one another and closer to our Savior. They bring us further “in.” As Aslan invited the children to come “further up and further in” in C.S. Lewis’ The Last Battle, come inside the library doors with me for a few moments to hear some stories.

As I step into the library each morning, flipping on the lights or entering to the sounds of beautiful music emanating from the instruments of rehearsing Rockbridge orchestra students, I am struck by the sight and smell of books—nostalgic memories flooding in from childhood days of library visits. These early-life visits being filled with wonder at what the pages hold from each book sitting on a shelf; imagining what journey each story will allow me to partake of or what tidbit of interesting information I can garner. Skip ahead a few years in memory to working in my university library…hoping during my shift that I’ll have some slow time in order to have a few minutes to comb through books in the special collections department or turn through the pages of a century-old newspaper…the corners of my mouth can’t help but turn up into a small smile as I pass through the Rockbridge library doors. After setting my things down, I retrieve the books that have been returned in the book drop, sort through books that have been donated, and collect the handwritten checkout slips, thrilled that the library has been used even during the “off hours.”

I think of the many anecdotes that have occurred over the past couple years in the library with students.

- I think of a kindergarten girl asking, “do you have any books about pink princesses?”

- Or, the 1st grade boy asking, “when are we going to get more books about snakes?”

- There are the instances of juniors or seniors telling me about their thesis topics and why they chose them.

- There’s the 9th grader’s eyes lighting up when they discover how many books we have about World War II!

- Then there’s the 3rd grader asking if we have any stories about dogs—she left the library with Because of Winn Dixie, only to come back a couple weeks later saying, “I love this book! As soon as I finish it, my mom said we could watch the movie together!”

- Then there’s a new upper school student perusing the library shelves and saying, “I love this series! I am definitely bringing in some books to donate!”

- Another instance is when a 2nd grader found a book on the shelf that had been consistently checked out by other students and exclaimed, “It’s finally mine!!!!”

- One of the sweetest things is seeing students in the hallway or after school saying, “Hi Mrs. St. Cyr! How’s the library?”

- There are dozens of other student stories, but I’ll end with a favorite. A junior kindergarten mom was in the building and expressed her thanks for our library. She said her daughter LOVES when her class visits the library each week. She told me she had been playing “library” at home with a table to check out books and had placed a bucket beside the table to serve as the “book return.” Oh, my heart.

I can’t help but share how amazing the Rockbridge faculty, staff, and community are as well. Through interactions and observations, I have experienced first-hand what it means to be part of a Christ-centered community.

- I think of Sam Ostransky bringing in theology classes and excitedly teaching them how to use Bible commentaries. Then he’ll stop by the library regularly to check out books for his small children at home—never neglecting to spend a moment at the library desk to give me an update on how my own children are doing in his classes.

- There’s Lysa Lytikainen or Caroline Master who spend a few minutes of work or a lunch break to get a moment by the sunshine streaming through the library windows. I absolutely love that Caroline is frequently pulling books off the shelves that she has looked up through the online library catalog prior to visiting.

- There are conversations with Andrew Menkis about Lewis or Tolkien.

- There’s Melanie Kaiss or Cheryl Mole bringing Mark Campbell into the library to check out books from his favorite Magic Treehouse series.

- There’s Bob Schingeck asking me to stage a joke with him at the circulation desk in order to elicit a giggle from a visiting class and brighten their day.

- There’s Matt Seufert, who provided me with the perfect scripture to use when I unexpectedly had to speak at a funeral.

- There’s Jacque Touhey, instrumental in the foundation of the library, checking in with wonderful ideas for helping the library thrive.

- There are Heidi Stevens and Laura Mathisen using their artistic and design gifts to discuss beautiful ways to make the library aesthetically pleasing to draw in students of all ages.

- There’s Therese Cooley using her art framing skills to repair a picture in the library that would have cost hundreds elsewhere.

- There are teachers who are at the ready and willing to help when I ask, “Can you bring your students to Story Time to share something they’ve learned?”

- When requesting recommendations for the book fair, there are book lists a mile long from Monica Godfrey or Matt Swanson.

- There’s a discussion with Monica Ault before the book fair about her recommendation of Anna Karenina and her love of the often difficult but profound Russian literature.

- There’s Kerry Anne Ward inviting me to a book club made up of mostly Rockbridge folk—where discussing Don Quixote or Kristin Lavransdatter with a savory treat in hand and a glass of sangria on the side just might be a little glimpse of heaven.

- There’s Stephen Unthank recommending publishers from which to request donations—and then receiving donations of many books from them!

- There’s Gretchen Geverdt continually bringing in donations because she makes it a point to go through books that the public library is disposing of to search for treasures.

- There’s Shannon Reich, to whom God must have given scheduling magic, who makes sure all the library events are perfectly placed on the calendar so as not to interfere with other events.

- There are beautiful moms who have used their time and gifts to make monthly story times special or design a gorgeous library bulletin board that evokes dozens of praises from passers-by.

- There are multiple parents who have stopped in the library and asked for our wish list so that they can be on the lookout for books to purchase and donate.

- There’s the added benefit of being in the library when classes bring in speakers and hearing talks about amazing topics from people like Chip Crane, Stephen Fix, Bryan Grube, or Matt Chwastyk.

- Being near the Beehive (library copy room)—may I please say that this active area is like no other workplace “water cooler” area I have ever witnessed? I’ve worked in several offices, and the places where people have the opportunity to converse are typically areas where people complain or gossip. The Beehive, however, is a place where there is uplifting conversation and offers of prayer and encouragement. It is a testament to how God is using this community.

- Jerry Keehner wheeling in carts of books from his personal library for students to use.

- An impromptu prayer time with Irma Cripe for a friend.

- A beautiful word of encouragement from Kim Ramirez or Chris Phillips. It is difficult for me to stop telling tales without writing a book!

Hopefully, these stories brought you “further up and further in” into life in the Rockbridge library. I think of how Aslan revealed himself to the Pevensie children through their experiences. They were ultimately drawn into the BEST story. At the end of The Last Battle, Lewis speaks of this story: “…the Great Story which no one on earth has read: which goes on forever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.” During a speech by Heidi Stevens at the library grand opening, she spoke of the time when the founding families of Rockbridge gathered together and what they envisioned. She said, “We longed for our children to recognize the great Story behind all good stories: the story of a King who is making all things right again and restoring his original pattern of what’s Beautiful, Good, and True.” May it be so.

Brenna St. Cyr has served in the Rockbridge library since its formation. She is currently pursuing her master's degree in Library Information Science and enjoys co-coordinating a food pantry at her church each week where she gets extensive community interaction. She has two children who attend Rockbridge, and she resides in Bowie, MD with her husband and children.

From our Library Grand Opening in September of 2022:

28 Faithful Years of Life Together

Mr. Roy Griffith, our headmaster, started his journey at Rockbridge Academy in 1997 as a 5th grade teacher joining this start-up classical Christian school. That marked the third year of the school and already it had grown from 23 students the first year to nearly 100. Few people had ever heard of classical education and even fewer of classical Christian education (CCE). Rare indeed were those willing to stake a career on it when no Rockbridge graduates even existed, and we had never taken a Grand Tour before.

Did this educational methodology actually work? We know the answer today is a resounding, yes, as CCE is now a fast-growing movement. But what was Mr. Griffith thinking 28 years ago? What led him to change careers from an architect to 5th grade teacher? What changes has he seen in CCE, and how is Rockbridge Academy poised to approach the next 30 years? Mr. Griffith shares his story, some of the challenges of the early years, and some words of advice to those just starting their classical Christian educational journey at Rockbridge Academy.

What were you thinking 28 years ago when you changed careers from an architect to a 5th grade teacher with four young children?

When I came to Rockbridge Academy, my wife, Donna, and I were chasing our first two of eventually, four kids and were deep into learning how to parent as Christians. Ever since we had brought our oldest home from the hospital, one thing persistently tugging on our souls was the conviction that if Ephesians was telling us to bring up our children, "in the fear and admonition of the Lord," it required us to be all in. We quickly awoke to how central education would be to forming not just their minds but the heart convictions our kids would carry into adulthood. So when I visited Rockbridge Academy during their opening year in 1995, I walked in thinking about an eventual school for my boys, but walked out personally captivated by the classical Christian vision. A thoroughgoing K-12 discipleship of the mind and heart anchored in the sovereignty of Christ and embracing the role of the whole family resonated in my soul. Months later, I couldn't get that vision out of my head, and I really believed the Lord gave me a burning desire to be part of that mission as a teacher. It wasn't an easy decision, as it meant long hours and a significant pay cut. When I proposed the career change to my wife, she responded wryly, "Well, we can try anything for a year." It was a defining moment. God has His ways, as one tentative year turned into twenty-eight.

So when I visited Rockbridge Academy during their opening year in 1995, I walked in thinking about an eventual school for my boys, but walked out personally captivated by the classical Christian vision. A thoroughgoing K-12 discipleship of the mind and heart anchored in the sovereignty of Christ and embracing the role of the whole family resonated in my soul.

How did you experience God's faithfulness as you took these steps of faith?

The early years were hard but rewarding. I had never before thought I would be a teacher, or thought I had a knack for it. But the Lord hollowed out a little space just for me, and I flourished in the classroom. At the same time, like many start-up Christian schools, all the teachers at Rockbridge literally worked below the poverty line, which had its own stresses. Meanwhile, God surrounded us with a precious school community who cared for our family. Food would show up at our door unannounced. Families took us along on their vacations. I remember one Christmas, a Rockbridge family left a gift anonymously at our front door each night for two weeks leading up to the holiday. We tried hard to catch them in the act, but they were really stealthy. It was both hilarious and heartwarming, and while we had our suspicions, we never found out who it was. My kids were spellbound by the surprise each night. Through it all, both the rewarding moments and the times of greatest stress and difficulty, we look back and see the Lord's hand. As I've come to realize, when God called us to this, He began a discipleship not just of my kids, but of our whole family.

Through it all, both the rewarding moments and the times of greatest stress and difficulty, we look back and see the Lord's hand. As I've come to realize, when God called us to this, He began a discipleship not just of my kids, but of our whole family.

What were some of the challenges you and those early teachers and administrators faced?

The greatest challenges by far came because none of us had been classically educated. While we were standing on the shoulders of a few slightly older schools trying to do the same thing, everything had to be built from scratch. From curriculum and lesson plans to traditions like feasts and history parades, to figuring out how to shape distinctively classical and Christian music and athletics programs, teachers and administrators were constantly trailblazing. Pioneering is tiring, often hard on relationships, and always fraught with mistakes. We look back on lots of mistakes. (We still make mistakes.) I think the Rockbridge Academy Core Values we articulated distilled from many hard-fought lessons in those early years and helped define who Rockbridge Academy has always aspired to be.

Have you seen the classical Christian education model change over the last 3 decades?

I would say that the classical Christian model itself has not fundamentally changed in three decades. Rather, I think our collective understanding of this education, one that had to be recovered from the distant past, has grown tremendously. In light of that fact, I think we have learned to approach the act of educating classically far more humbly than we used to.

Some would argue that true classical education cannot exist without Christ. What are your thoughts?

At the risk of losing any of our aforementioned humility, I'd say, "absolutely!" But to back up, answering this question requires us to think historically. Certainly, the educational model of ancient Greeks and Romans developed in a pagan context, and those societies raised some of the greatest philosophers and statesmen in Western History. Early Christians saw what a powerful tool the Greco-Roman culture had developed. But they also realized that all good things only come by the common grace of the Creator, and that Jesus Christ is sovereign over all knowledge. So what we know today as classical education with all the beautiful trappings is something brought to its fullness in the Christian Middle Ages, which purposely threaded the model with deeper truths of the Scriptures. So, while it's possible to just teach classically, we need to remember how empty the wisdom of the world can be.

How do you see Rockbridge Academy growing and poised to contribute in the next 30 years?

We are in an exciting time in classical Christian education. The resiliency of this model of education compared to others became very apparent during COVID, so classical Christian schools and homeschool tutorials are now popping up everywhere and flourishing. Because Rockbridge Academy has almost 30 years of trial and error in this space, God has positioned us to have a leading impact on this part of God's kingdom. In many ways, that is already happening through our Summer Teacher Training Conference, hosting classical Christian student teachers, and our semi-annual spring ACCS Auxilium conference for start-up schools. We are actively collaborating with greater organizations like ACCS (Association of Classical Christian Education) and SCL (Society for Classical Learning) to expand upon that influence. But as we too experience growth within, our campus is only so big. I tell people, I never want our campus to grow so big that I can't eventually learn everyone's name. So that means further growth could take many forms, including supporting the classical Christian homeschool movement, planting a satellite campus, or expanding specialized programs for both neurodivergent students or students with more profound disabilities. This is why we must remain prayerful. I'm confident the Lord will lead in a way that causes Rockbridge Academy to continue to accomplish its mission to Christian families.

What advice do you have for young families and teachers starting their CCE journey at Rockbridge Academy?

Go to church. Study God's Word. Actively pray. Raise your kids in the fear and admonition of the Lord with intentionality. Love on your children's teachers and get to know them. Walk humbly before God as you figure out who your kids are, and once you think you have, prepare for them to change as they grow. Know that doing all of these things, including sending your child to a Christian school is not a formula for success; it is simply acting as obediently as you can. So finally, trust God with the results of each day and each decade they are under your roof.

Roy Griffith joined Rockbridge Academy as a 5th grade teacher in 1997. He transitioned to grammar school principal in 2012 and then in 2015 took on the role of interim headmaster to headmaster in 2016. Roy's wife, Donna, has served in various roles in Rockbridge history and today uses her gifts in multiple areas of coaching and care coordination for the elderly. Roy and Donna's four children are Rockbridge alumni: Elyse (2019) living locally and finishing her business degree at UMD, Grace (2018) married to Nathan Harrison (2017) and living in Charlotte, NC, Drew (2015) married to Anna (Krauss, 2015) living in Phoenix, AZ, and Nate (2013) married to Emily (Comeau) and teaching upper school science at Elizabeth Seton High School in Bladensburg, MD.

Roy Griffith joined Rockbridge Academy as a 5th grade teacher in 1997. He transitioned to grammar school principal in 2012 and then in 2015 took on the role of interim headmaster to headmaster in 2016. Roy's wife, Donna, has served in various roles in Rockbridge history and today uses her gifts in multiple areas of coaching and care coordination for the elderly. Roy and Donna's four children are Rockbridge alumni: Elyse (2019) living locally and finishing her business degree at UMD, Grace (2018) married to Nathan Harrison (2017) and living in Charlotte, NC, Drew (2015) married to Anna (Krauss, 2015) living in Phoenix, AZ, and Nate (2013) married to Emily (Comeau) and teaching upper school science at Elizabeth Seton High School in Bladensburg, MD.

A Part of Our Rockbridge DNA: A Reflection on Faculty Morning Prayer

As students come into the building each morning, they hear a strange sound echoing throughout the hallways. It's an unfamiliar sound in schools and buildings to be happening at 7:30 in the morning: sometimes louder, sometimes softer, and sometimes a higher or lower pitch. And then it abruptly stops about three minutes later. The sound comes from Mrs. Kennedy's Physics classroom. But the students hear it every day, so they no longer raise their eyebrows and ears to figure out what it is. It's completely normal to them.

What the students hear each morning is the sound of their teachers singing a hymn a cappella. Since the door is left ajar, the sound travels. From the entrance of the school, you can just make out murmurs set to pitch; as students walk further into the building, the words become more recognizable. School hasn't started yet, so students are unloading book bags and already nibbling away at their lunches, casually hanging out with friends with heels up on their locker doors. To them, hearing adult men and women singing full voice is not strange to them. It's just what their teachers do.

#87: Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God Almighty! / Early in the morning our song shall rise to thee; / Holy, Holy, Holy, merciful and mighty! / God in three Persons, blessed Trinity!

Each morning the Rockbridge faculty and staff gather together to sing a hymn and pray together for our students, families, and alumni. This is absolutely one of my favorite things we do. Here's how we do it.

When the bell rings at 7:30, someone picks out a number from a blue Trinity Hymnal. We've all picked one up from a bookrack as we've entered, so we're ready. It's a bonus when we're accompanied by a piano or a flute, but we're normally a cappella. Some of us try to sing harmonies—others succeed. And if it’s one of those hymns with the extra verses written beneath the final music staff, we sing all the extras too.

The collection of blue Trinity Hymnals with a solitary gold cross on the front have been gifted to us from various churches as they have updated to the newer red hymnals of the same design. Inside the front cover are stamps of the names of the donating churches. That our hymnals which allow us to sing together do not all come from one church but from several reminds me of the fellowship of families which belong to a myriad of church congregations and denominations but come together to form one Rockbridge. The Trinity Hymnal has been a new hymnal to me, but it has nearly all of my favorites.

#122: O ye heights of heav'n, adore him; / Angel hosts, his praises sing; / All dominions, bow before him, / And extol our God and King.

That our hymnals which allow us to sing together do not all come from one church but from several reminds me of the fellowship of families which belong to a myriad of church congregations and denominations but come together to form one Rockbridge.

After singing, we pray for current Rockbridge families and for alumni, selecting about five or six families each day. There's even a binder labeled "STAFF MORNING PRAYER LIST" to make sure we don't miss anyone, moving alphabetically through a roster of family names throughout the year. If you are an alumni, please know that we still pray for you by name. Your teachers delight in remembering you. For current families, please know that we pray for your entire household by name. As an Upper School teacher, praying for Grammar School students is how I have come to know the students who will one day be in my classroom.

If you are an alumni, please know that we still pray for you by name. Your teachers delight in remembering you.

We also take prayer requests for the faculty and staff for the day. It is here that we have shared in some of the greatest joys in each other's lives while also lamenting the greatest of sorrows. In a way, to pray for someone is to truly know them because it is to properly see them, their joy, or their sorrow in relation to God's ever-present care. Similarly, to be prayed for is to be known. It has meant so much to me on the days when I have asked my colleagues to pray with and for me.

It is here that we have shared in some of the greatest joys in each other's lives while also lamenting the greatest of sorrows.

The hymn, the prayer requests, the fellowship of prayer. This all happens in about ten minutes. And I'm so glad it does. It would be so natural to start the day together but to do so merely for the sake of making announcements and reminders about the day. And while we do sometimes have those, the focus is on preparing our hearts for the people and the learning of that day. As the school begins to be filled with students, it is also filled with prayer asking God to guide, to protect, to nurture our students.

I wanted to know when this rhythm began and how it had evolved, so I went about asking those teachers who were starting school days fifteen, twenty, or twenty-nine (!) years ago. All of them said the same thing: it’s one of those things that everyone remembers doing but doesn’t remember when or how it started. It struck me that singing to God and praying to him are just a part of the DNA of Rockbridge. Just as we don't remember learning to brush our teeth or how to tie a knot, at Rockbridge we sing to God and pray to him because it is part of the fabric of who we are.

#492: Take my voice, and let me sing, / Always, only, for my King. / Take my lips, and let them be / Filled with messages from thee.

It struck me that singing to God and praying to him are just a part of the DNA of Rockbridge. Just as we don't remember learning to brush our teeth or how to tie a knot, at Rockbridge we sing to God and pray to him because it is part of the fabric of who we are.

Education Must Be More Than Just Classical

"Virtues are hard things,” quipped National Review writer Daniel Buck in a recent opinion article entitled “The Virtues of Classical Schools.” Buck continued: “Fail a test of courage or act unwisely and virtue will demand justice or forgiveness. Values are subjective, virtues objective. The former is a preference, the latter a firm statement of right and wrong, true and false, good and evil.”

Examining one Hillsdale-launched classical charter school, Lake County Classical Academy (LCCA), Buck argues that although classical schools bear some similarities to their public counterparts, classical educators stand apart from our culture in that they are not afraid to incorporate structure and objective values into their pedagogy, policies, and classroom life.

As a graduate of a K–12 classical Christian school and a current teacher at another classical Christian school, I appreciated much in Buck’s article. Indeed, while much of public education rests on slippery, subjective foundations, classical education can rest on objectivity and uphold structure and hierarchy in the classroom in a way that benefits students and prepares them to comprehend truth and virtue.

Yet, as I finished Buck’s article, I couldn’t help feeling that he failed to explain significant attributes of the school he profiled and the classical-education movement in general. For instance: Who gets to define what virtue is, what “right and wrong, true and false, good and evil” are? What is the foundation from which these schools draw the objective truths they teach? For public charter schools such as LCCA, these questions cannot be fully answered, since such questions require a religious framework. One cannot define goodness and truth apart from an ultimate source of goodness and truth.

One cannot define goodness and truth apart from an ultimate source of goodness and truth.

Classical charter schools like LCCA have bloomed around the country, thanks to Hillsdale’s Barney Charter School Initiative and to the success of programs such as Great Hearts Academies and Valor Education. But the origins of today’s classical-school movement — origins that Buck did not mention — lie in a distinctly Christian understanding of classical education. As Emma Green documented in an extensive New Yorker article published earlier this year, today’s classical-education movement began with four Christian schools inspired by the vision of education held by Dorothy Sayers, a Catholic, and launched in the 1980s. In the 21st century, classical education has grown more pluralistic, thanks to the rise of classical charter schools and private classical schools without religious affiliation.

But classical education without Christ is not only oxymoronic, it is futile in an ultimate sense.

This portion of the article was republished with permission. Click HERE to continue reading Sarah Reardon's article in the National Review.

Sarah Reardon (class of 2020) is a graduate of Grove City College with degrees in English and classical studies. She wrote for GCC's newspaper, The Collegian, and the cultural magazine, Cogitare Magazine. She has contributed articles to Front Porch Republic, The American Conservative, National Review, and several online literary magazines.

Ancient History and the Modern Student

To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain forever a child.

~Marcus Tullius Cicero

Roman statesman, philosopher, and orator, Marcus Tullius Cicero, said, “To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain forever a child.” If we do not know who and what came before us, we cannot learn from the mistakes and successes of others, and will, therefore, remain foolish in our thinking and actions. One of the primary goals of a good education is to produce morally responsible men and women who understand and value their civic duties for society to function well. Additionally, education should form the affections to love the Biblical standards of truth, goodness, and beauty so that the student desires to imitate God. Studying ancient history within the classical framework viewed through the lens of Scripture is a valuable pursuit for the modern student.

Building upon what the student already learned in the grammar stage, the Rockbridge seventh grader learns ancient history—from Creation to the fall of the Roman Republic. By studying the past, the student begins to have a greater understanding of how our present age and worldviews were shaped, how lessons of the ancients are relevant today, and how studying history leads to a deeper knowledge of oneself and of God’s sovereign plan.

By studying the past, the student begins to have a greater understanding of how our present age and worldviews were shaped, how lessons of the ancients are relevant today, and how studying history leads to a deeper knowledge of oneself and of God’s sovereign plan.

For the modern student who wonders about why the world is the way it is today, the classical teaching methodology of ancient history will answer his question. By 7th grade, the student has already formed certain presuppositions that determine how he makes decisions and interacts with reality. By studying the past, the student gains a greater understanding of how our present age was shaped. Ideas of the past have consequences. For example, the Athenians argued against the Melian idea of freedom and justice, that “the strong do what they will and the weak suffer what they must” as they attempted to expand their empire. This idea, “survival of the fittest,” had tremendous consequences throughout history which points to how our present age was shaped. The student considers this idea by reading the Melian Dialogue, identifying and analyzing arguments on both sides, and contrasts it to Scripture which teaches us to care for the weak and oppressed and offers a different idea of freedom and justice. If the student understands the problems of the past and their attempted resolutions, it helps him understand today and where we may be headed in the future.

As the modern student of ancient history learns how our present age was shaped, he also wonders about what lessons he can learn from long-deceased men of ancient times. After all, haven’t we “advanced” as a society and as human beings since then? Through the classical methodology, time-tested vices, virtues, beliefs, and practices are taught. Civic and moral codes of the ancients reveal how decisions and actions have consequences and can be used today as either “base things to avoid or fine things to imitate” (Livy). The student learns to be civically and morally literate by judging past actions and applying those lessons today.

Our founding fathers continually turned to the ancients for lessons in vice and virtue. For example, the founders studied the lives of men like Julius Caesar, who sought to advance his own power, and Cincinnatus, who willingly gave up his power. To the founders, one was a villain, the other a hero. These vices and virtues are the same today as they were then. They are time-tested. Have we “advanced”? Our sinful human nature says, “No.” This is what we have in common with all mankind throughout history. The modern student realizes this as he studies the ancients and learns of vices to be aware of and virtues of men and women upon whose shoulders we can stand.

Finally, the modern student of ancient history wonders how he can come to a deeper knowledge of himself and God’s sovereign plan of salvation for fallen human beings. First, classical Christian education considers the framework of the student and how he was designed by our Maker. In the dialectic stage, the student begins to distinguish between good and evil and make judgments. In making these moral distinctions, he gains a finer understanding of himself and the world. Age-appropriate examples of good and evil throughout history are taught and confront the student with his sinful nature, the need for repentance, and the need for a Savior. The modern student who examines his life honestly will see himself in others who have gone before him and create a desire in him to love God’s standards of what is true, good, and beautiful and make the right choices.

Furthermore, history finds its existence and relevance exclusively in God and His will for His creation. History cannot be known apart from the knowledge of God and His relation to the universe. History begins at Creation. After the Fall, in times of darkness, before Christ, the modern student learns how God is setting the stage to reveal “a light for revelation.” The light for which man has been searching. Christ, the light, who comes during turmoil and uncertainty, transforms the world. For history to make sense and why it matters to the modern student today, it is imperative that he or she understands the magnitude of this transformation, its effect upon humanity, and that every single event is the manifestation of God’s providential plan. All of history before Christ points to the cross and therefore, should be studied.

For history to make sense and why it matters to the modern student today, it is imperative that he or she understands the magnitude of this transformation, its effect upon humanity, and that every single event is the manifestation of God’s providential plan. All of history before Christ points to the cross and therefore, should be studied.

Through studying ancient history, the modern student learns about western heritage and man’s quest for justice and freedom—out of which comes true justice and freedom in Christ. Ultimately, by studying ancient history, it is the hope that it will lead the modern student to deeper and richer worship of Christ and equip him to be a light to the lost. People and events of ancient history are just as relevant as the issues we face today—both have something in common—sinful human nature. The Apostle Paul writes about examples of men who were written down as warnings for us, men who were idolaters, and perished for it. Let us not be as children who do not heed the lessons of the past, rather let us learn from those who have gone before us to teach us what we ought to do.

Jean Grev has taught dialectic Ancient and European History at Rockbridge Academy since 2012. She graduated with a BA in communications arts and sciences with an emphasis on public speaking and rhetoric and a minor in business management from Michigan State University. She resides in Annapolis, Maryland with her husband; her three children are in the Rockbridge Academy classes of 2020, 2021, and 2025.

Unexpected Lessons on Grand Tour

Grand Tour is a very unique experience that Rockbridge Academy students get to enjoy. On this academic trip, students spend two and a half weeks traveling to many parts of Greece and Italy such as Athens, Corinth, Rome, Sienna, and Florence. They get to actually see the places that they have learned about for so many years and understand the way the ancients thought through the physical things they left behind. True to the classical Christian method, though, the goal of Grand Tour is not merely to grow students intellectually, but to teach students to trust in God's redemptive work. God taught me many lessons through my experiences on Grand Tour. He did this through revealing my sin, showing me His abounding mercy, and exemplifying His greatness.

The first way that God worked in me on Grand Tour was through revealing my sin to me. Through this He gave me the opportunity to grow as one of His children. While on Grand Tour, we were in a new city almost every night, away from home, taking in large amounts of information, and constantly spending time with our classmates. While all these things were great blessings, they also opened the door for certain temptations. After conversations with some of my classmates, I found that many of us struggled with the sin of comparison. God made each of us uniquely and blessed each of us in different ways, but so often I found myself coveting the talents, relationships, and reputations of my peers. This is not the way that a child of God who has been blessed so much by Him should behave.

God helped me to fight this temptation through journaling. Mr. Keehner required us to write one page of reflection on how we saw God at work each day. This process kept me from dwelling in my own thoughts and forced me to write them out and think about how I should respond in light of what Christ had done for me. I needed to rely on His sovereign will in order to learn contentment.

Another lesson that God taught me while I was on Grand Tour was how His mercy applies to my day-to-day life. While we were on the bus one morning, Mrs. Ball read to us Psalm 103:10, which says, “He does not deal with us according to our sins, nor repay us according to our iniquities.” Now as a Christian, I already knew this, but I had not been living as if I knew it. I knew that God would not condemn me because Christ had been condemned for me, but I lived holding my breath, waiting for God to send temporal consequences for my sin, which would, no doubt, ruin my trip. One evening I realized, as I was looking out at the sun falling beneath the Adriatic Sea, that God had blessed me with yet another amazing day, yet I had fallen short of what He called me to time and time again. The verse that Mrs. Ball had read came back to me, and I was brought to tears by the abounding mercy of God. Each day He continued to delight in blessing me when what I really deserved was punishment.

The last way that God grew me on Grand Tour was through exemplifying His greatness. When I sat at the top of the mountain at Delphi and looked out over the sprawling mountain ranges, the misty olive groves below, and the wildflowers which grew out of the face of the rock, I realized how small everything in my life was in comparison to the greatness of God. It brought back words to my mind of a song that I had not sung since I was in elementary Sunday school. While the words of this song are so simple, I continued to meditate on the mysteries behind them for the rest of the trip.

Lord, You are more precious than silver;

Lord, You are more costly than gold;

Lord, You are more beautiful than diamonds,

And nothing I desire compares to You.

Lord, Your love is higher than the mountains;

Lord Your love is deeper than the seas;

Lord, Your love encompasses the nations,

And YET, You live right here inside of me.

It truly is amazing that a God so vast and great dwells in the souls of sinful mortals like us. He continues to sanctify us through His holy word and the experiences we have in our lives. He graciously reveals to us our sins, but readily showers us with mercy. His greatness is revealed to us through all His works, and I was truly blessed to have seen him at work in such a unique way on Grand Tour.

Jessi Wenger is a senior at Rockbridge Academy who has been a part of the school since she was in kindergarten. Her favorite areas of study are theology, literature, and philosophy. In her free time, she enjoys participating in performing arts, such as the Rockbridge musical and variety show, along with taking and teaching dance classes. She also enjoys writing poetry, cooking, reading, gardening, and making homemade soaps and candles.

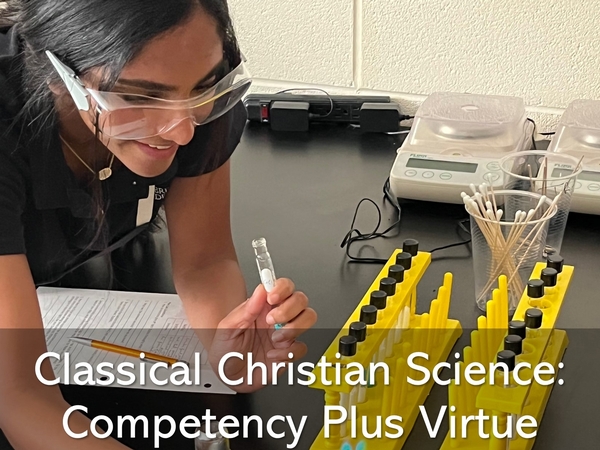

Classical Christian Science: Competency Plus Virtue

"Science is the search for the truth.”

– Linus Pauling, founder of Quantum Chemistry & Molecular Biology